|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

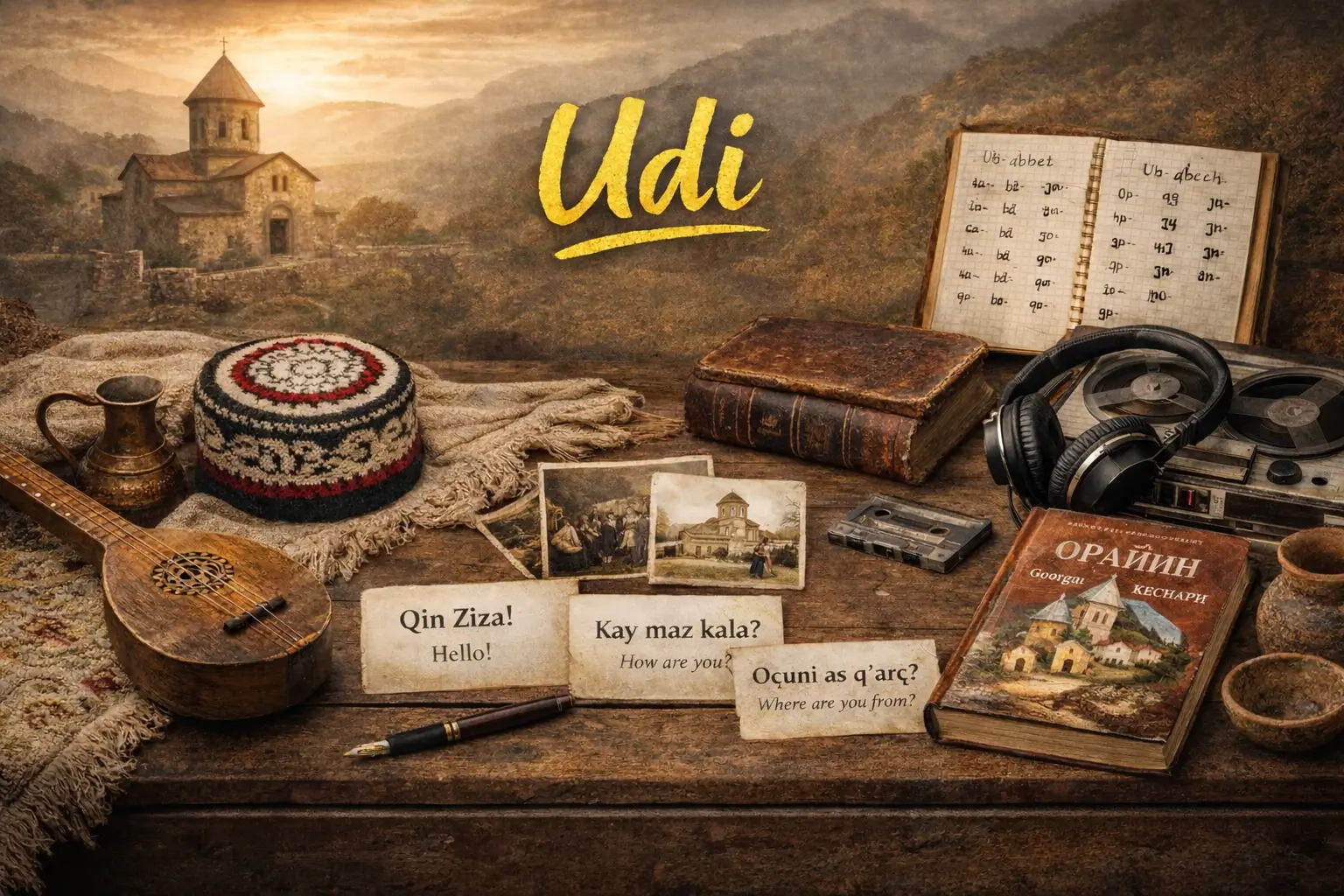

Udi isn’t just an endangered language. It’s a living trace of a people whose history stretches back through the Caucasus.

Spoken by a small community in Azerbaijan and parts of the diaspora. Udi has survived empires, borders, and centuries of pressure from bigger languages. That’s the miracle.

The problem is simple: survival isn’t the same as transmission.

When a language stops being used at home, in jokes, arguments, lullabies, everyday life. It doesn’t “fade”. It breaks. Fast.

Udi people and their historical significance

The Udi are a small Indigenous people of the eastern Caucasus.

Best known for preserving the Udi language and a distinct Christian heritage centred today around Nij (Azerbaijan) and Zinobiani (Georgia).

Their historical weight is bigger than their numbers:

- A living link to Caucasian Albania: Udi communities are seen as one of the closest modern continuations of that ancient kingdom’s cultural legacy.

- Survival through pressure: centuries of empire, border shifts, and dominant languages have pushed assimilation, yet Udi identity has endured.

- High-value heritage: because the language is rare and endangered. Udi carries outsized importance for understanding the Caucasus’s history and diversity.

The role of language and culture in shaping identity

Language and culture don’t just express identity. They build it.

- Language is your everyday identity toolkit: how you name family, show respect, tell jokes, argue, pray, flirt, grieve. It carries the “default settings” of belonging.

- Culture gives the shared script: traditions, values, food, music, stories, faith, and the unspoken rules of “how we do things”. It tells you who counts as “us”, what your history means, and what you’re expected to pass on.

Together, they shape identity in three big ways:

- Belonging: speaking (or not speaking) a community language can mark you as inside, outside, or “in-between”.

- Memory: language stores history in place names, folklore, and the meanings you can’t translate cleanly.

- Continuity: when culture is practised and language is used at home, identity stays lived.

Historical Background of the Udi People

Before you can understand why the Udi language is endangered, you need the people behind it.

The Udi story is one of deep roots in the eastern Caucasus and repeated disruptions that reshaped:

- where communities lived,

- how they organised themselves,

- and which parts of their identity could survive in public.

Origins, settlement patterns, and historical migrations

The Udi are one of the oldest surviving Indigenous peoples of the eastern Caucasus. Often linked to the population of Caucasian Albania (in today’s Azerbaijan and neighbouring areas, not the Balkans).

For centuries, Udi communities were rooted in a handful of villages. With Nij and Vartashen (now Oğuz), the best-known centres.

Over time, economic change, political pressure, and conflict pushed migration outward. Including the creation of Zinobiani in Georgia by Udi refugees from Vartashen in the 1920s.

Traditional cultural practices, beliefs, and social organisation

Udi identity has long been anchored in community life, family networks, and church tradition. Religion isn’t just belief here. It has functioned as an organising structure: a calendar, a social hub, a shared memory bank.

Culturally, the Udi sit at a crossroads. Centuries of life alongside Armenian, Iranian, Turkic and Russian spheres shaped everyday practices. From material culture to customs.

While the community still maintained a distinct language and local traditions that signalled “we are Udi”.

Key historical events that have shaped the Udi community

Udi history is a story of continuity under constant reshaping forces. The fall of Caucasian Albania and later imperial rule altered religious administration and language use in public life. Increasing long-term pressure towards assimilation.

In the modern period, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict hit especially hard. Udi communities from Vartashen/Oğuz were displaced in the early 1990s. Accelerating diaspora movement and weakening intergenerational transmission in some families.

The Udi Language: A Unique Linguistic Heritage

Udi isn’t “just another minority language”.

It’s a rare surviving branch of the eastern Caucasus’ linguistic world, and for linguists. It’s a crucial key for understanding the region’s deeper past.

For the Udi community, it’s something even simpler: the sound of home.

Structural features and defining characteristics of the Udi language

Udi is part of the Northeast Caucasian family (the Lezgic branch), and it’s often described as a southern outlier within that wider group.

What makes it stand out on the page?

- SOV word order is common (subjects and objects tend to come before the verb).

- It shows an ergative pattern (a grammatical way of marking “who did what to whom” that differs from English).

- It has a rich case system (often described as around 11 cases in modern descriptions). Meaning nouns change form to show roles like location, direction, and relationship.

- Udi is also shaped by long contact with neighbouring languages (including Armenian and Iranian languages). Which has left fingerprints in its grammar and vocabulary.

Comparison with neighbouring and related languages

Udi sits in a crowded neighbourhood and that’s part of the story.

Within its Northeast Caucasian relatives, Udi shares the “Caucasus signature”. Complex morphology and fine-grained grammatical marking. It also has quirks that reflect its unique history and contact position.

Next to Azerbaijani (a Turkic language) and Armenian (Indo-European), Udi can feel very different.

Not because it’s “more complicated”, but because it encodes meaning in different places (suffixes, cases, clitics) and has absorbed features through centuries of close interaction.

The role of language in artistic and cultural expression

A language stays alive when it has somewhere to live: in stories, rituals, humour, songs, nicknames, and everyday talk.

For Udi, that cultural role is especially visible in community tradition and revival work. Including efforts to document and teach the language and renew public use in places where Udi is still spoken.

Learn Udi: Practical Phrases, Patterns, and Mini-Drills

Udi is easiest to learn when you treat it like a spoken skill first and a “grammar subject” second. Build a small set of high-utility phrases, then recycle them in dozens of situations.

Start with a “core kit” you can use immediately

Learn these as whole chunks. Don’t overthink the grammar yet.

- Hello: Xeirq’anbaki (Хеиркъанбаки)

- Welcome: Usumun hari / Usumnan hari

- Good morning: Savax xeir

- Good afternoon: Berezarin xeir

- Good evening: Biyəs xeir

- Goodbye: Dirist’oğon

Polite + survival:

- Yes / No: Ho / Tə

- Sorry: Bağişlamişba

- Thank you: Dirist’baka (also Gele dirist’baka)

- I understand / I don’t understand: Zu va q’amişzu / Zu va q’amiştezu

Use “conversation glue” to keep speaking (even with tiny vocab)

These are the phrases that let you learn in the moment:

- What’s your name? Vi s’i hik’ə?

- My name is… Bez(i) s’i …

- Do you speak Udi? Udin muz avanu?

- How do you say ___ in Udi? Udin muzin … hetər pesebako?

Practice script (say it daily):

Xeirq’anbaki. Vi s’i hik’ə? Bez(i) s’i Alex. Zu va q’amiştezu… Udin muzin “water” hetər pesebako? Dirist’baka.

(Hello. What’s your name? My name is Alex. I don’t understand… How do you say “water” in Udi? Thank you.)

Build sentences by recycling one pattern

Pick one frame and swap one word each day. For example:

Frame: “How do you say ___ in Udi?”

- Udin muzin “bread” hetər pesebako?

- Udin muzin “tea” hetər pesebako?

- Udin muzin “help” hetər pesebako?

You’ll learn faster because you’re training retrieval + speaking. Not just memorising lists.

Learn a few anchor words that appear everywhere

Even one or two “anchor” words help you understand real texts and examples.

- “water” = xe (used in Udi grammar examples)

Now you can start noticing it in the wild, especially in example sentences and case tables.

Use real dictionaries that include examples

Because Udi resources are scattered, use tools that give example phrases, not just single-word translations:

- Glosbe (English–Udi / Udi–English) often includes example sentences and sometimes audio.

- Freelang’s Udi dictionary is useful for building a basic word bank.

Mini-routine that actually works (15 minutes)

- 3 min: read your core kit aloud (greetings + thanks + “I don’t understand”)

- 5 min: run the practice script 5 times, then faster

- 5 min: add 3 new nouns (from Glosbe/Freelang) and plug them into Udin muzin … hetər pesebako?

- 2 min: record yourself saying Xeirq’anbaki → Bez(i) s’i … → Dirist’baka and compare day-to-day

Current Status of the Udi Language

Udi is still spoken, but its “centre of gravity” is shrinking.

In most places, it survives as a home language, while public life (school, work, media) runs in bigger regional languages. Which changes what the next generation grows up using.

Estimated number of speakers and demographic distribution

Speaker counts vary by source and by what counts as “speaking” (fluent vs partial). The big picture is consistent: a small speaker base, concentrated in a few communities.

A conservative, source-backed total is about 5,750 speakers worldwide:

- roughly 3,800 in Azerbaijan (2011),

- 1,860 in Russia (2020),

- and around 90 in Georgia (2015).

Social, political, and economic factors contributing to endangerment

Udi’s risk isn’t about “forgetting”. It’s about domains of use collapsing.

Studies describe Udi as a family/home language. While the dominant state language takes over in education, administration, and wider community life.

Key pressures show up:

- Bilingualism turning one-way (the bigger language expands. Udi gets confined to private settings).

- Mixed marriages reducing transmission when the household default becomes the majority language.

- Migration and dispersal breaking the dense, everyday speaker networks a small language needs to survive.

The impact of globalisation, urbanisation, and modern education

Globalisation and urbanisation don’t “attack” a language. They reward mobility.

If jobs, study, and opportunity sit in majority-language spaces. Families prioritise the language that opens doors.

Education is the sharpest edge when schooling is in the dominant language. Udi gets pushed into evenings and weekends, and that’s rarely enough for strong literacy or confident teen/adult use.

Cultural Significance of the Udi Language

Udi isn’t valuable because it’s “rare”

It’s valuable because it carries the community’s working memory. The stories people tell, the morals they repeat, the rituals that mark time, and the everyday humour that only makes sense in the original language.

Language as a repository of folklore, oral history, and tradition

Folklore is where a small language stays strong, because it gives people a reason to keep using it.

In Udi communities, tradition isn’t just preserved in museums.

It’s kept alive through songs, dances, games, legends, and household parables, many of which are passed down through speech rather than writing.

The connection between language, memory, and collective identity

Udi identity is linked to where and how the language is used: home life, community gatherings, and especially religious and cultural continuity.

When Udi is spoken in these settings, it does something bigger than communication. It signals belonging and keeps shared history “active” rather than symbolic.

Examples of Udi proverbs, songs, stories, and rituals

Udi culture isn’t just “heritage”. It’s language doing real work: teaching, remembering, blessing, warning, celebrating. Here are concrete, citable examples you can actually point to.

Proverbs (spoken wisdom)

Proverbs often survive longest because they’re useful: short, repeatable, and easy to pass on.

- “A tree without branches does not throw a shadow.” (recorded as a Udi proverb in Udi-language sources cited by linguists).

- Udi also has biblical-style proverb texts in modern Udi translations. For example, Udi Proverbs 4 contains lines like: “Şot’aynak’ ki, şoroxe vi yəşəyinşi orayin.” (Udi text as published).

Songs and hymns (language as performance)

Music is one of the quickest ways a minority language becomes public again, something you can sing, share, and feel.

- Udi singer-songwriter Diana Govasari describes composing and performing Udi-language material, including songs titled “The Song for Lord” and “Sa vard”, created with her mother Larisa Govasari.

- She also notes audience interest in Udi religious hymns and psalms, with people requesting lyrics and background.

Stories (narrative tradition)

Stories are where language carries values: what counts as brave, shameful, funny, clever — and what a community wants children to internalise.

- Documented Udi texts with full glosses and translations exist, including everyday narrative-style instructions (which are gold for learners because they show real sentence structure).

- Example opening lines from a Udi recipe text include: “alisa, aq’-a qo qoqla… xaˁxaˁ-p-aˁ.” with a running English translation.

- Udi writer-educator Georgy Kechaari’s “Orayin” is described as including Udi folklore such as a fairy tale, a legend, a proverb, and jokes.

Ritual life (language + calendar)

Ritual is where minority languages often “cling on” the hardest: weddings, church life, seasonal gatherings, and community ceremonies.

- Udi culture is explicitly documented through works on traditional Udi wedding ceremonies and community life, highlighting how ritual practice preserves identity markers and language use.

- Reporting and community accounts repeatedly point to Nij as a key centre of Udi life. The kind of tight-knit setting where ceremonial language and intergenerational transmission have a fighting chance.

Efforts to Revitalise the Udi Language

Revitalisation work for Udi is less about big “national programmes” and more about rebuilding daily use: at home, in schools, in community spaces, and in culture.

The most effective efforts tend to do one thing well. Make Udi usable again.

Community-led initiatives and grassroots preservation efforts

Grassroots work usually starts with the basics: getting people to speak Udi in more places than the kitchen.

In practice, that looks like community-led cultural revival, local organising, and public-facing projects that make Udi feel normal (and valued) again.

You can see this in the growing cultural focus around Udi heritage and the push to maintain identity markers in key centres like Nij.

Educational programmes, language classes, and teaching materials

School matters because it creates routine exposure and signals that the language is worth learning.

- In Zinobiani (Georgia), Udi has been taught in primary classes since 2015, and recent fieldwork confirms Udi is still a home language there.

- In Azerbaijan, sources describing Udi life in Nij highlight the existence of Udi-language educational materials and schooling that includes the native language alongside the dominant language(s).

Collaboration with linguists, researchers, and cultural institutions

For small languages, collaboration is often the difference between “we mean well” and “we have recordings, dictionaries, and teaching content people can actually use”.

- Major documentation initiatives (e.g., DOBES/MPI projects) explicitly include Udi. Producing recordings and corpora that preserve speech, narratives, and cultural context.

- Broader programmes like ELDP (SOAS/Arcadia-funded). They support endangered-language documentation and make resulting collections accessible through archives.

Challenges Facing Udi Language Preservation

Udi doesn’t disappear because people stop caring. It disappears when daily life stops needing it.

For small languages, the danger is rarely one dramatic event. It’s a slow squeeze: fewer places to speak, fewer reasons to speak, fewer young people hearing it often enough to own it.

Socio-economic pressures affecting everyday language use

Economic opportunity tends to pull people towards cities, wider networks, and majority-language workplaces. When families move or commute, Udi often gets confined to “home-only” moments.

- Migration and dispersal weaken the tight speaker networks Udi depends on.

- Work and social mobility reward fluency in dominant languages, so Udi becomes optional.

- Mixed-language households can shift the default to the majority language. Especially once children enter school.

Dominance of majority languages in public life and education

This is the biggest structural issue. Public life runs on majority languages: school, paperwork, exams, media, jobs, smartphones. Even motivated families struggle when almost every “high-status” domain is elsewhere.

When schooling is in a dominant language, children learn which language counts for success. Udi then competes with homework, television, and social media.

Intergenerational gaps and shifting language attitudes

Endangerment accelerates when the language becomes associated with the past rather than the future.

- Older speakers may be fluent, but younger speakers become passive understanders. (They can follow, but don’t reply in Udi).

- Teens may avoid using Udi publicly if it feels “out of place” or “not useful”.

- Parents sometimes switch languages out of love, to give children the strongest chance in school and work, but that choice can break transmission within one generation.

How You Can Help

You don’t need to be Udi to support Udi.

What matters is helping create the conditions where the language can be recorded, taught, used, and respected. Without turning it into a novelty.

Supporting language documentation and revitalisation projects

The most practical help is support for work that produces lasting resources: recordings, texts, dictionaries, and lessons.

- Donate or fundraise for endangered-language documentation and community teaching where possible (even small monthly support helps sustain fieldwork, archiving, and materials).

- Share and use archived materials: listen to recordings, cite them, and link people to primary sources instead of second-hand summaries.

- If you have skills, offer them: editing, web design, audio cleanup, subtitling, layout, curriculum formatting. These are often bottlenecks for small-language projects.

Raising awareness through education, media, and advocacy

Awareness works when it’s specific, not vague.

- Write or post about what Udi is, where it’s spoken, and why it’s endangered, using concrete details rather than “sad language loss” generalities.

- If you create content, include accurate pronunciation clips, short explainers, and sources and avoid sensational claims about “last speakers” unless you can verify them.

- Encourage schools, libraries, and language communities to include endangered languages in their programming.

Helpful Websites for Learning the Udi Language

Here are some useful websites for learning about Udi / finding phrases, texts, and recordings:

- Omniglot (Udi phrases + writing/alphabet): quick starter phrases and basics for learners.

- Glosbe (English ↔ Udi dictionary): translations + example phrases, and often pronunciation/audio.

- UMass Amherst (Alice C. Harris) – Udi texts PDFs: real Udi texts with linguistic formatting (great for serious learners).

- The Language Archive (MPI) – search “Udi”: recordings and materials (including “Udi proverbs” and other cultural content).

- ECLING Project: Udi (Goethe University Frankfurt / TITUS): background + links into documentation resources.