In one small riverside village in southwestern Ethiopia, the last speakers of Ongota still whisper words no other people on Earth understand. Their language, once part of a thriving culture, now balances on the edge of silence.

Ongota isn’t just rare. It’s unique. Unrelated to any known language family, it carries the story of a people who endured isolation, change, and time itself. Preserving it means keeping alive a voice the world is only just beginning to hear.

Origins and History of the Ongota People

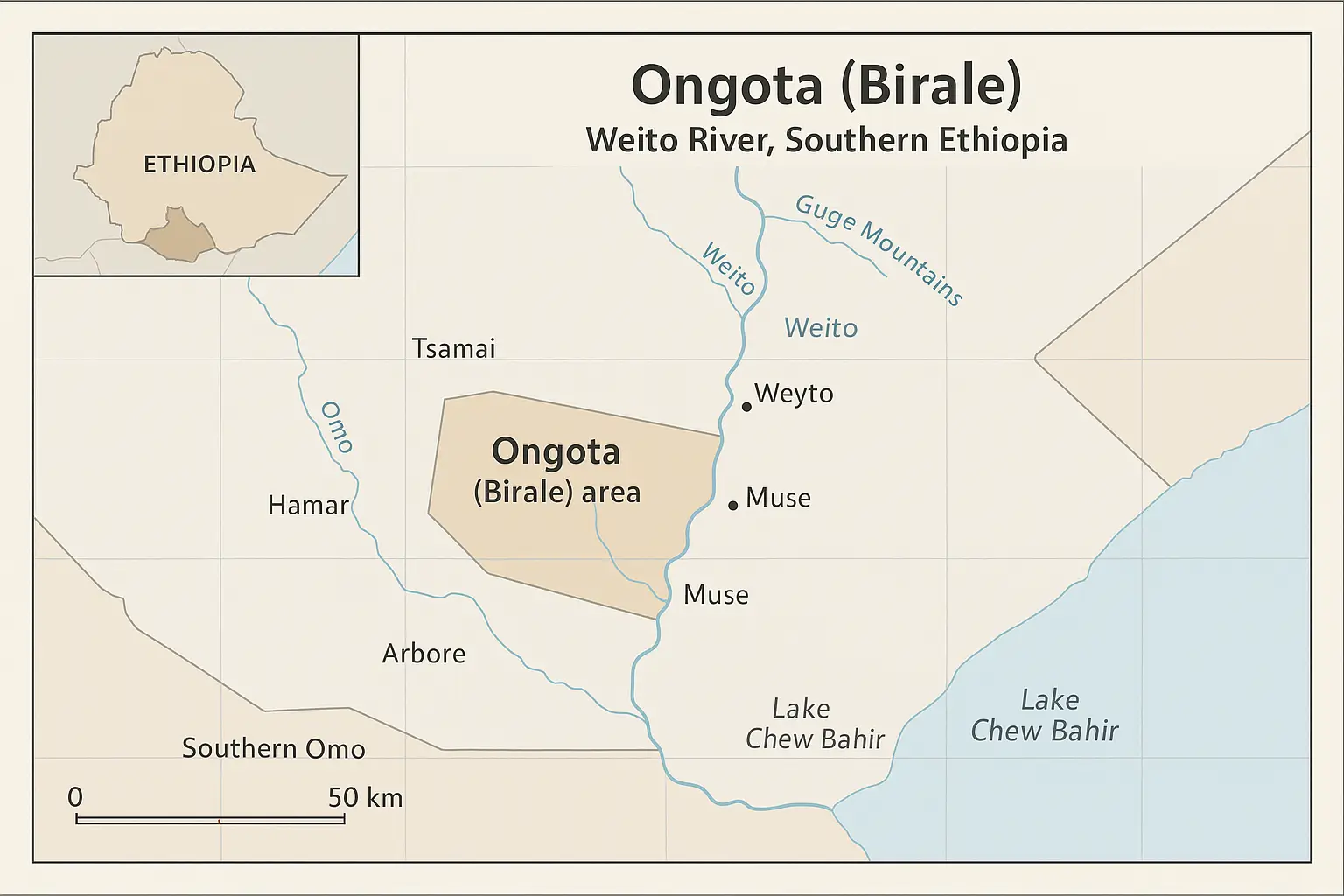

The Ongota people, also referred to as Birale, are, sadly, among the least-known communities in Ethiopia. Their homeland lies along the Weito River in the country’s remote southwest, where history, language, and culture have grown together into a story of the people’s resilience.

Though their numbers are now critically small, the Ongota carry a legacy that offers rare insight into Ethiopia’s diverse past.

A Small Community on the Weito River

Along the fertile riverbanks of the Weito lives one of the world’s most endangered communities. Their story is not only about survival in isolation but also about preserving identity in the face of cultural pressure.

Early Roots and Settlement

The Ongota descend from older pastoral and fishing groups who settled in the Omo–Tana region long before larger ethnic communities arrived.

Oral history recalls that the Ongota once occupied wider lands but were gradually displaced or absorbed by groups such as the Ts’amakko and Amhara. Today, only one small village remains.

Life on the Margins

Historically, the Ongota lived as farmers and fishers, depending on seasonal rains and the Weito River for survival.

Their marginal location kept them beyond the reach of Ethiopia’s powerful kingdoms and empires, allowing them to maintain an identity distinct from dominant groups, like the Amhara and Oromo.

A History Entwined with Mystery

The greatest mystery in Ongota history is within their language. It does not fit neatly into Ethiopia’s main language families: Afroasiatic or Nilo-Saharan.

Some linguists argue it is a unique isolate, while others believe centuries of cultural contact shaped it into a hybrid tongue. This mystery reflects the community’s layered past and its resilience against cultural erasure.

Why Their Story Matters

The Ongota people are more than a historical curiosity. They are guardians of a fragile cultural thread that has endured against the odds, reminding us that even the smallest communities can hold stories as vast and significant as entire nations.

Where Ongota Is Spoken

The Ongota language is spoken in only one place on Earth, a tiny village along the Weito River in southwestern Ethiopia. Unlike other Ethiopian languages that spread across regions and ethnic groups, Ongota has always been geographically confined. This adds to its rarity and vulnerability.

The Weito River Region

The Ongota people live on the eastern banks of the Weito River, near Lake Turkana and not far from the Omo Valley. This is an area known for its cultural and linguistic diversity. This region is home to dozens of ethnic groups, but Ongota stands out as one of the smallest and most endangered.

Isolation and Neighbouring Communities

Geographic isolation has both preserved and endangered Ongota. The community lives close to the Ts’amakko, Hamar, and Amhara peoples, whose larger populations and stronger Cultural influences have gradually pushed Ongota speakers away from their mother tongue.

Today, many Ongota use Ts’amakko as a second language, while younger generations increasingly adopt Amharic, Ethiopia’s national language.

A Language Bound to a Single Village

Unlike Oromo, Amharic, or Somali, which span vast areas and millions of speakers, Ongota exists only within one small settlement of fewer than 100 people. This extreme localisation means that the language’s survival is entirely dependent on the vitality of a single community.

If Ongota speakers stop passing it on to their children, the language could vanish from the world within a single generation. Putting the language in danger.

Linguistic Classification and Mysteries

The Ongota language is one of the most puzzling tongues in Ethiopia and in the world. Unlike other Ethiopian languages that can be clearly linked to major families such as Afroasiatic or Nilo-Saharan, Ongota defies neat classification.

For linguists, it represents both a mystery and an urgent call to study a language before it disappears forever.

A Language Out of Place

Most languages in Ethiopia fall within two major families: Afroasiatic (which includes Amharic, Oromo, and Somali) and Nilo-Saharan (spoken by groups around the Omo Valley and beyond).

Ongota, however, doesn’t clearly belong to either. Early research suggested it might be Afroasiatic, but later studies pointed to Nilo-Saharan traits, or even a mixture of both.

A Case for a Mixed Language

Some scholars argue that Ongota may be the result of a language shift. This means the Ongota people could once have spoken a Nilo-Saharan language but gradually adopted Afroasiatic structures while retaining traces of their older tongue.

This layered identity mirrors the community’s history of cultural contact and survival among larger neighbours.

The Isolate Hypothesis

Other linguists have gone further, suggesting Ongota could be a linguistic isolate. A language with no proven relatives anywhere in the world.

If true, this would make Ongota even more unique, carrying clues about human migration and settlement in the Horn of Africa that no other language can reveal.

Why It Matters

The unresolved debate around Ongota’s classification makes it more than a curiosity; it is a key to understanding Ethiopia’s deep history of human movement, contact, and cultural exchange.

Yet with so few speakers left, there is a real risk that the mystery of Ongota will never be solved. Preserving recordings and documentation is not just a linguistic task. It is a race against time.

Phonology and Grammatical Features of Ongota

While Ongota has never been fully documented, the studies that do exist reveal a language with intriguing sound patterns and structural traits. Even with so few speakers left, Ongota shows how unique a small, isolated language can be in its phonology and grammar.

Sound System (Phonology)

Although only fragments of Ongota have been recorded, linguists have identified several notable traits in how the language sounds.

These features hint at a system that is both simple and layered with subtle distinctions:

- Consonants and Vowels: Ongota makes use of a relatively small set of consonants compared to larger Ethiopian languages. Its vowels, however, show clear distinctions in length and tone. Features that can change meaning in subtle ways.

Tone and Stress: Like many African languages, Ongota appears to use tone to distinguish words. For example, a single syllable may mean two different things depending on whether it is pronounced with a high or low pitch. - Borrowed Sounds: Contact with neighbouring languages such as Ts’amakko and Amharic has introduced additional sounds, especially in newer vocabulary.

Grammar and Structure

Beyond its sounds, Ongota’s grammar shows fascinating patterns that distinguish it from surrounding languages. Researchers have noted several recurring traits in how sentences, verbs, and nouns are formed:

- Word Order: Ongota seems to prefer Subject–Object–Verb (SOV) word order, aligning with many Afroasiatic and Nilo-Saharan languages of the region.

- Gender and Number: Nouns often mark distinctions of gender (masculine/feminine) and number (singular/plural). These are expressed through affixes or tonal changes rather than separate words.

- Verb System: Ongota verbs carry complex information about tense, aspect, and mood. Speakers can convey whether an action is completed, ongoing, or hypothetical with subtle morphological shifts.

- Pronouns: Personal pronouns are distinct and do not resemble those of neighbouring languages, supporting the idea that Ongota may have an independent lineage.

A Blend of Influences

What stands out is how Ongota grammar carries traces of both Afroasiatic and Nilo-Saharan systems.

For instance, its verb morphology shows parallels to Cushitic languages, while some plural forms resemble patterns in Surmic tongues. This mix further fuels the debate about Ongota’s origins and classification.

Why should you care?

Every sound and grammatical rule in Ongota is valuable evidence in solving one of Africa’s greatest linguistic puzzles.

Without systematic documentation, these features could vanish without ever being fully understood, taking with them insights into the history of language in the Horn of Africa.

Factors Leading to the Decline of Ongota

The Ongota language has reached a point of critical endangerment, with only a handful of speakers left. Its decline is not the result of a single cause but rather a combination of social, cultural, and economic pressures that have shaped the community over generations.

Pressure from Neighbouring Languages

The Ongota people live alongside much larger groups such as the Ts’amakko and Amhara. Daily interaction has led to widespread bilingualism, with younger Ongota often adopting Ts’amakko or Amharic instead of their ancestral tongue. Over time, this shift has weakened the transmission of Ongota to new generations.

Declining Number of Speakers

Ongota is spoken by fewer than 20 people, and most are elderly, hence the designation of the language being almost extinct.

With no children learning the language, intergenerational transfer has effectively stopped. This demographic reality is one of the strongest indicators that Ongota is on the brink of extinction.

Social and Cultural Marginalisation

As one of Ethiopia’s smallest ethnic groups, the Ongota have historically lacked political or social influence. Their marginal status has made it harder to preserve their traditions and has often forced them to assimilate into dominant neighbouring cultures.

Economic and Environmental Challenges

Living along the Weito River has tied the Ongota people to subsistence farming and fishing, but environmental changes, droughts, and shifting land use have put pressure on their livelihoods. In times of hardship, practical needs often outweigh cultural preservation, accelerating language loss.

The Modernisation Effect for Ongota

National policies, schooling, and media in Ethiopia overwhelmingly promote Amharic as the official language.

For the Ongota, participation in modern education and the wider economy often requires abandoning their mother tongue in favour of more dominant languages.

Documentation and Preservation Efforts

Though Ongota is critically endangered, it has not gone entirely unnoticed. Linguists and preservationists have made attempts, limited but important, to record the language before it disappears completely.

These efforts highlight both the challenges and the urgency of safeguarding Ongota’s fragile legacy.

Early Academic Attention

Ongota first drew wider interest in the late 20th century, when researchers noted its unusual features and uncertain classification.

Scholars such as Harold C. Fleming and others documented word lists, grammatical notes, and recordings, bringing international awareness to this small Ethiopian language.

Fieldwork and Recordings

Because so few people speak Ongota, researchers have conducted fieldwork only sporadically and often with difficulty.

However, small collections of recordings, songs, oral traditions, and conversational samples exist in academic archives. These resources provide invaluable material for future study, even if people no longer speak the language.

Challenges to Preserve Ongota

The efforts to save Ongota face steep obstacles:

- Tiny Speaker Base: With fewer than 20 speakers, mostly elderly, there are virtually no opportunities for language revitalisation unless these people teach the language.

- Community Shift: Younger generations prefer Ts’amakko or Amharic, meaning Ongota is no longer being passed down.

- Limited Resources: Preservation projects in Ethiopia often prioritise larger endangered languages, leaving Ongota at the margins.

What is the role of technology?

Digital tools have opened new possibilities for preservation. Even a few hours of high-quality audio or video recordings, shared online, could keep Ongota accessible to linguists, historians, and future generations.

Open-access archives and collaborations with international universities may be the most realistic way to safeguard what remains.

Why Every Record Matters

While Ongota may not survive as a living community language, every document, recording, and analysis contributes to humanity’s understanding of linguistic diversity.

Preserving Ongota is not just about saving words. It’s about respecting the cultural identity of one of Ethiopia’s smallest and most overlooked peoples.

Why Preserving Ongota Matters

When a language disappears, the loss goes far beyond words. It takes with it entire ways of seeing, thinking, and relating to the world.

Only a handful of people may speak Ongota, but the language carries centuries of memory, culture, and identity that no other language can replace.

A Window into Human History

Ongota preserves traces of ancient migration, trade, and contact among the peoples of the Horn of Africa. Every sound and grammatical pattern holds clues about how cultures evolved and interacted. Losing it would erase part of the puzzle of Ethiopia’s and humanity’s linguistic history.

Cultural Identity and Dignity

For the Ongota people, their language is not just a tool of communication; it is the soul of their community.

It encodes their songs, their oral stories, and their names for the land and seasons. Preserving Ongota protects their dignity and ensures people remember them as more than a vanished tribe.

Lessons for the World

The story of Ongota connects to a wider pattern of language loss around the world. It mirrors the plight of hundreds of small languages worldwide.

Protecting Ongota reminds us that linguistic diversity is a form of human resilience. Each language offers a unique philosophy, a different lens on what it means to be human.

Take Practical Steps to Get Involved With Ongota

Preserving a language like Ongota isn’t just the work of scholars or governments. It’s something that individuals, students, and global citizens can all play a role in. Even small contributions help preserve this endangered Ethiopian voice for the future.

1. Support Language Documentation Projects

Organisations such as the Endangered Languages Project, ELAR (Endangered Languages Archive), and DoBeS actively collect and preserve materials from dying languages. Donating, sharing their work, or even volunteering remotely helps keep projects like Ongota with language documentation alive and accessible.

2. Amplify Awareness

Simply learning about Ongota and sharing its story matters. Write about it, post it, discuss it in classrooms or language forums. The more visibility Ongota gains, the greater the pressure for cultural and academic institutions to prioritise its preservation.

3. Encourage Inclusive Research

Academic interest often follows awareness. Support initiatives that push for collaborative fieldwork, where linguists partner directly with Ongota speakers and local Ethiopian researchers to document the language ethically and comprehensively.

4. Promote Linguistic Diversity in Education

Teachers, language learners, and content creators can highlight the value of smaller languages in their materials. Encouraging curiosity about lesser-known tongues, from Ongota to Ainu to Yaghan, helps normalise the idea that every language is worth studying.

5. Advocate for Digital Preservation

Technology can be a lifeline for endangered languages. Share, archive, or help subtitle existing Ongota recordings; support open-access repositories; or participate in global translation initiatives that make these resources available to everyone.

6. Reflect and Reconnect

Even if you never visit Ethiopia, preserving Ongota begins with valuing the diversity of human expression. Every time we protect a language, we protect a worldview, and affirm that no culture is too small to matter.

Ongota Language FAQs

What is the Ongota language?

Ongota is an extinct or nearly extinct language that was once spoken by a small community in south-western Ethiopia, near the lower Omo Valley.

Where was Ongota spoken?

A very small community spoke Ongota in Ethiopia, primarily around the Weyto (Weito) River area, alongside other ethnic and linguistic groups.

Is Ongota an extinct language?

Linguists generally consider Ongota extinct or functionally extinct. The last fluent speakers likely died in the early 21st century, and people no longer use the language in daily communication.

What language family did Ongota belong to?

Linguists debate Ongota’s classification. Some linguists have linked it to the Afroasiatic family, while others argue it may have been a language isolate due to its unusual structure and limited data.

Why is Ongota important to linguistics?

Ongota is important because it highlights how quickly languages can disappear when speaker numbers fall too low. Its uncertain classification and minimal documentation make it a key example in discussions about language extinction and the urgency of linguistic preservation.