|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

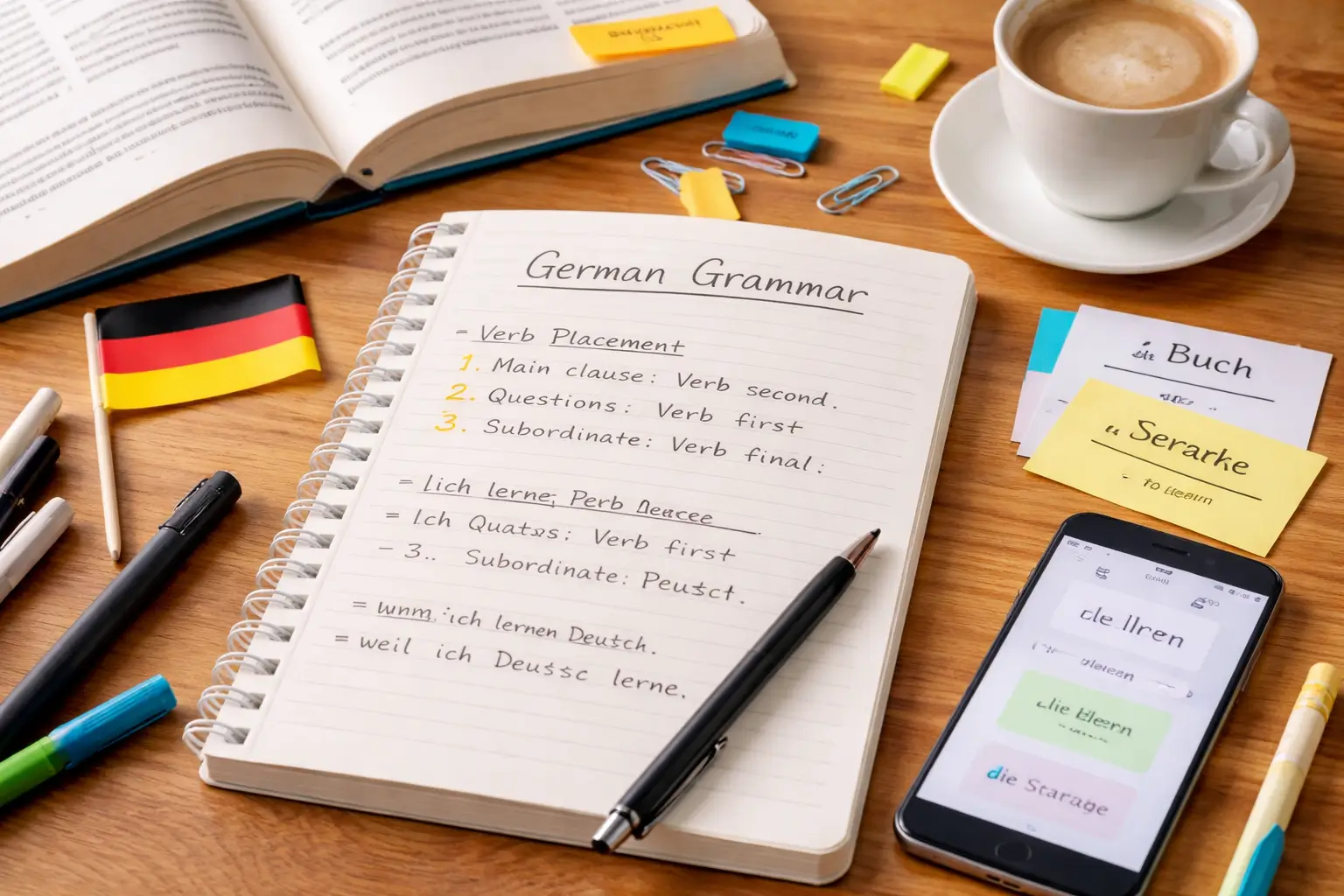

German sentence structure often feels intimidating to learners.

Word order in German is driven by clear patterns rather than guesswork. Yet many explanations focus on rules without showing how they actually function in real sentences.

This simple guide breaks German sentence structure down into practical, usable ideas, using everyday examples you’ll recognise from real conversation. You’ll learn how German sentences are built and why verbs seem to “move”.

Importance of understanding German sentence structure

German sentence structure is essential because it underpins everything else in the language.

Vocabulary alone is not enough. Without control of word order, even correct words can produce sentences that sound confusing or unnatural to native speakers.

German relies heavily on structural signals, especially verb position, to indicate meaning. A small change in word order can turn a statement into a question, shift emphasis, or completely alter how a sentence is interpreted.

How can mastering sentence structure improve communication and comprehension?

Mastering sentence structure transforms how you communicate and understand German. Instead of guessing meaning or translating word by word, you follow the language’s built-in logic as it unfolds.

Clear word order lets you express ideas confidently and naturally, even with simple vocabulary. In comprehension, it helps you track verbs, link clauses, and spot emphasis instantly. Making long sentences easier to process and conversations far less tiring.

The Basics of German Sentence Structure

German sentence structure follows clear, reliable patterns.

Once you understand how sentences are built and how each part functions, German stops feeling random and starts feeling predictable.

The fundamental components of a German sentence

At its core, a German sentence is built from the same basic elements as English:

- a subject,

- a verb,

- and often an object or other complements such as time, place, or manner.

- What makes German distinctive is not what elements it uses, but where they appear.

German relies on position to signal meaning. The verb, in particular, plays a central organisational role.

Rather than floating freely, it occupies specific slots in the sentence, which determine whether you are making a statement, asking a question, or adding extra information.

Roles of subject, verb and object

Because German uses case endings to mark grammatical roles, word order can shift without confusing. It is something English cannot do as easily.

- Subject: the person or thing acting. This does not always come first in a German sentence.

- Verb: the engine of the sentence. In main clauses, the verb typically appears in the second position. Regardless of what comes first.

- Object: the person or thing affected by the action. Often placed after the verb, but flexible depending on emphasis and sentence type.

Comparison with English sentence structure

English relies heavily on a fixed subject–verb–object order to convey meaning. German, by contrast, uses verb position and case marking to organise sentences. This allows for more flexibility. He also means learners must pay close attention to structure.

For example, starting a sentence with time or place is normal in German. But it forces the verb to move into second position. Something that never happens in English.

The Role of the Verb

The verb is the structural anchor of a German sentence. More than any other element, verb placement determines whether a sentence is grammatical, clear, and natural.

Understanding where the verb goes is one of the fastest ways to improve both accuracy and comprehension in German.

Explanation of verb placement in German sentences

In main clauses, German follows the verb-second rule.

This means the finite verb appears in the second position, regardless of what comes first in the sentence. The first position can be the subject, a time expression, an object, or even a full phrase.

In questions, the verb moves to the first position, while in subordinate clauses, the verb is pushed to the end of the clause.

Main verbs versus auxiliary verbs

German often uses auxiliary verbs such as sein (to be), haben (to have), and werden (to become) to build tenses, the passive voice, and the future.

When an auxiliary verb is present, it takes the finite verb position, while the main verb moves to the end of the clause in its infinitive or past participle form.

This split verb structure can feel unusual to English speakers, but it follows a consistent logic: the auxiliary carries tense and agreement, while the main verb carries meaning.

Examples of different verb placements in various sentence types

Once you see the verb as the organising centre rather than just another word, German sentence structure becomes far easier to predict and control.

- Statement (verb second): Ich lerne Deutsch.

- (I am learning German.)

- (I am learning German.)

- Statement with time first: Heute lerne ich Deutsch.

- (Today, I am learning German.)

- (Today, I am learning German.)

- Question (verb first):Lernst du Deutsch?

- (Are you learning German?)

- (Are you learning German?)

- Sentence with auxiliary verb: Ich habe Deutsch gelernt.

- (I have learned German.)

- (I have learned German.)

- Subordinate clause (verb final): …, weil ich Deutsch lerne.

- (… because I am learning German.)

- (… because I am learning German.)

Word Order in Statements

German statements follow a clear underlying structure, but they allow more flexibility than English when it comes to emphasis and style.

The standard pattern first makes these variations easy to recognise and use correctly.

Detailed look at standard word order (SVO) in declarative sentences

In neutral statements, German often appears to follow a subject–verb–object (SVO) order. Similar to English.

However, what truly defines German declarative sentences is not SVO, but the verb-second rule. The finite verb must appear in the second position, while the subject usually comes first by default.

This creates sentences that look familiar to English learners. Even though they are governed by a different structural principle.

Examples of simple statements and their translations

In each case, the subject comes first, and the verb comes second. Creating a neutral, unmarked statement.

- Ich lerne Deutsch: I am learning German.

- Er liest ein Buch: He is reading a book.

- Wir besuchen unsere Freunde: We are visiting our friends.

Explanation of variations in word order for emphasis

German allows other elements, such as time, place, or objects, to appear in the first position for emphasis or clarity.

When this happens, the verb still remains in second position, and the subject moves after it.

- Heute lerne ich Deutsch: Today, I am learning German.

- Zu Hause arbeitet er.: At home, he works.

These variations do not change the basic meaning. But they shift the focus of the sentence.

Questions and Inversion

Forming questions in German is straightforward once you understand the role of verb position.

Instead of adding extra words or changing tone alone, German uses inversion, a clear shift in word order, to signal that a sentence is a question.

How questions are formed in German

German questions are primarily formed by placing the finite verb at the beginning of the sentence.

This applies to both spoken and written German and provides an unambiguous structural cue that a question is being asked.

Question words such as wer (who), was (what), wann (when), and wo (where) naturally take the first position, followed immediately by the verb.

Explanation of subject–verb inversion in yes/no questions

In yes/no questions, the verb comes first and the subject follows it.

This inversion replaces the verb-second pattern used in statements and is one of the most consistent features of German sentence structure.

No additional helper verbs are needed, unlike in English.

- Kommst du heute?: Are you coming today?

- Hast du Zeit?: Do you have time?

Examples of question formation using everyday scenarios

German questions rely on structure rather than intonation alone. Recognising verb position makes both asking and understanding questions far easier in real conversations.

- Lernst du Deutsch?: Are you learning German?

- Isst ihr zu Hause?: Are you eating at home?

- Wann beginnt der Kurs?: When does the course begin?

The Importance of Cases

German uses cases to show how words function within a sentence. While this can seem intimidating at first, cases are what give German its structural clarity and flexibility.

Once you understand them, sentence structure becomes more logical and far less dependent on rigid word order.

Four German cases (nominative, accusative, dative and genitive)

German has four grammatical cases, each signalling a different role:

- Nominative: marks the subject of the sentence (who or what is performing the action).

- Accusative: marks the direct object (who or what is directly affected).

- Dative: marks the indirect object (to whom or for whom something happens).

- Genitive: shows possession or close relationships between nouns.

These cases are expressed through articles, pronouns, and adjective endings. Rather than changes to the noun itself.

How cases affect sentence structure

Because cases identify grammatical roles, German can move sentence elements without losing meaning. The subject does not always need to come first, and objects can be reordered for emphasis or clarity.

This is why German sentences may look unfamiliar but remain precise. The listener knows who is doing what to whom, even when word order changes.

Examples demonstrating case usage in sentences

Understanding cases shifts your focus away from translating word order and towards recognising grammatical roles.

A key step in mastering German sentence structure.

- Nominative: Der Mann liest: The man is reading.

Accusative: Der Mann liest das Buch: The man is reading the book. - Dative: Der Mann gibt dem Kind das Buch: The man gives the book to the child.

- Genitive: Das ist das Buch des Mannes: That is the man’s book.

Using Adverbs and Adjectives

Adverbs and adjectives add precision and nuance to German, but their placement follows clearer rules than many learners expect.

Understanding where these descriptive elements belong helps your sentences sound natural rather than translated.

Placement of adverbs and adjectives in sentences

Adjectives appear directly before the noun they describe and must agree with it in case, gender, and number. Their position is fixed. Their endings change depending on the grammatical context.

Adverbs, by contrast, are more flexible. In main clauses, they usually appear after the verb, but their relative order follows a common pattern.

Time, manner, and place information often follow the sequence time – manner – place, giving German sentences a predictable internal flow.

Examples of sentences with different adverb and adjective placements

Here, adjectives stay tightly linked to nouns. While adverbs move to shape emphasis and clarity.

- Ich habe heute viel gearbeitet: I worked a lot today.

- Sie spricht sehr ruhig: She speaks very calmly.

- Wir treffen uns morgen im Café: We are meeting tomorrow at the café.

- Er hat einen guten Plan: He has a good plan.

Tips for using descriptive language effectively

Mastering adverbs and adjectives allows you to add detail without disrupting structure. An essential step towards fluent, confident German.

- Focus on correct verb placement first, then add descriptive elements around it.

- Use adverbs sparingly at early stages to keep sentences clear and controlled.

- Learn common adjective endings in context rather than as isolated tables.

- Pay attention to how native speakers order information, especially in longer sentences.

Subordinate Clauses

Subordinate clauses are one of the defining features of German sentence structure.

They allow you to connect ideas, give reasons, express conditions, and add detail. They also trigger one of the most important word-order changes in the language.

What subordinate clauses are and their function

A subordinate clause is a clause that depends on a main clause and cannot normally stand alone. It adds information such as cause, time, condition, or contrast.

In German, subordinate clauses are easy to identify because they follow a strict structural rule: the verb goes at the end of the clause.

This verb-final position signals to the listener that the clause is subordinate and helps organise longer, more complex sentences.

Conjunctions that introduce subordinate clauses

Subordinate clauses are usually introduced by subordinating conjunctions, such as:

- weil (because)

- dass (that)

- wenn (if / when)

- obwohl (although)

- während (while)

- damit (so that)

These conjunctions immediately push the verb to the end of the clause.

Examples of sentences with subordinate clauses and their structure

In each example, the main clause follows normal verb placement, while the subordinate clause ends with the verb.

Once you expect the verb at the end, longer German sentences become much easier to follow and far less intimidating.

- Ich lerne Deutsch, weil ich in Deutschland arbeiten möchte: I am learning German because I want to work in Germany.

- Sie sagt, dass sie keine Zeit hat: She says that she has no time.

- Wenn es regnet, bleiben wir zu Hause: If it rains, we stay at home.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

German sentence structure is highly systematic, but many learners struggle because they apply English patterns where German uses different logic.

Recognising these common mistakes early makes your progress faster and far less frustrating.

List of frequent errors learners make with German sentence structure

Many difficulties with German sentence structure come from a small set of repeat mistakes rather than a lack of grammar knowledge.

- Ignoring verb position: placing the verb too late or forgetting the verb-second rule in main clauses.

- Keeping English word order: especially after time or place expressions (Heute ich lerne Deutsch).

- Forgetting verb-final position in subordinate clauses: a very common error in longer sentences.

- Misplacing separable verbs: forgetting to move the prefix to the end of the sentence.

- Relying on word order instead of cases: assuming position shows meaning rather than case endings.

Encouragement to practise with examples

The best way to overcome these mistakes is through active practice. Start with simple sentences, change one element at a time, and check how the verb responds.

With repeated exposure and correction, German sentence structure quickly becomes automatic rather than something you have to consciously calculate.

German Sentence Structure FAQs

What is the most important rule in German sentence structure?

The most important rule is verb position. In main clauses, the finite verb must be in the second position, regardless of what comes first in the sentence.

Why does the verb go to the end in some German sentences?

This happens in subordinate clauses. Conjunctions like weil, dass, and wenn push the verb to the end to signal that the clause depends on another sentence.

Is German word order flexible or strict?

German is structurally strict but surface-level flexible. Verb position and case markings are fixed, but other elements can move for emphasis without changing meaning.

Do I need to memorise all the cases to build sentences correctly?

You don’t need to master them all at once, but understanding how cases signal grammatical roles is essential. They reduce reliance on rigid word order and prevent ambiguity.

How can I practise German sentence structure effectively?

Start with short, simple sentences. Change one element at a time, such as adding a time phrase or a subordinate clause, and observe how the verb position changes. Repetition builds intuition quickly.