|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

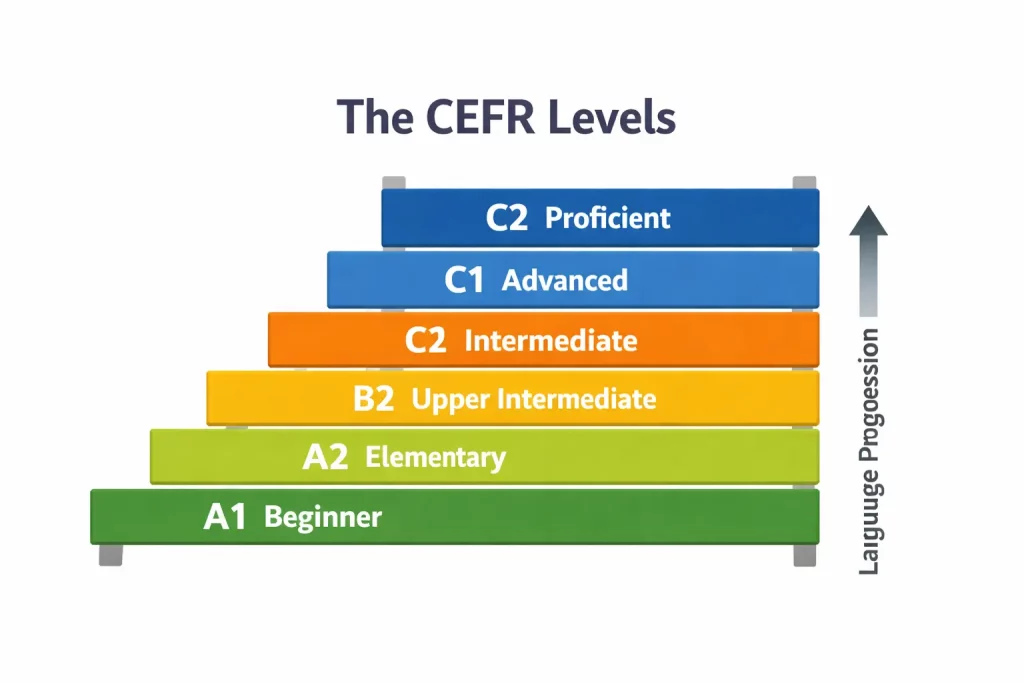

Language learning levels can be confusing, especially when labels like A1, B2, beginner, and advanced are used differently across apps, courses, and textbooks.

One platform says you are a beginner, another calls you intermediate, and suddenly, it is unclear what your language level actually means or how close you are to progressing.

This guide explains language learning levels from A1 to C2, how the CEFR system works, and how to judge your real, usable language level, not just what a test says.

Who This Article Is For?

This article is for anyone who wants a clearer, more realistic understanding of their language level.

More importantly, without jargon or guesswork. It’s especially useful if you:

- Feel unsure whether you’re a beginner, intermediate, or somewhere in between

- See labels like A2 or B1 everywhere, but don’t know what they actually mean in practice

- Want to track real progress in speaking, listening, reading, and writing

- Are learning independently and need a clear structure to guide your next steps

- Are returning to a language after a long break and want to reassess your level

By the end of this guide, you will be able to identify your real language level, understand what A1–C2 actually mean in practice, and decide confidently whether to consolidate or move up.

Language Learning Levels at a Glance (A1 to C2)

| CEFR band | Language Learning Levels | What it means in real life |

| Basic user | A1–A2 | Simple everyday tasks, short exchanges |

| Independent user | B1–B2 | Real conversations, most situations manageable |

| Proficient user | C1–C2 | Nuance, precision, complex input |

Understanding Language Learning Levels

Language learning levels exist to bring structure and clarity to what can otherwise feel like a vague learning journey.

Instead of guessing whether you’re “good” or “not very good” at a language, levels provide shared reference points that describe what learners can realistically understand, say, read, and write at different stages.

They help learners, teachers, and institutions speak the same language when it comes to progress.

What is the common language proficiency framework?

The most widely used system is the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). It divides language ability into six clearly defined levels, based on real-world communication skills rather than grammar knowledge alone.

CEFR is used globally by schools, universities, language apps, employers, and exam boards because it focuses on practical ability:

- how well you can follow conversations,

- express ideas,

- and function in everyday situations.

Other frameworks exist, but most map back to CEFR in some way. Making it the closest thing to a universal standard.

Different language learning levels (A1 to C2)

CEFR groups learners into three broad bands: Basic, Independent, and Proficient users.

- A1 -A2 (Basic User): You can understand and use simple phrases, handle everyday situations, and communicate basic needs. At A2, conversations become more flexible, but vocabulary and accuracy are still limited.

- B1 – B2 (Independent User): You can manage most real-life situations, hold conversations on familiar topics, and understand the main ideas of spoken and written content. B2 is often where learners begin to feel genuinely comfortable using the language.

- C1 – C2 (Proficient User): You can use the language fluently, spontaneously, and precisely. At these levels, you understand nuance, idiomatic expressions, and complex texts, with C2 approaching near-native competence.

Why do the levels exist?

Language learning levels exist to make progress measurable and meaningful. Without them, learners often overestimate or underestimate their ability. This leads to frustration or stagnation.

Levels also create consistency. They allow teachers to design appropriate courses, employers to set language requirements, and learners to compare resources fairly.

Most importantly, they break the long journey to fluency into achievable stages, making it feel possible rather than overwhelming.

CEFR Language Levels vs Real-World Ability

CEFR levels are designed to describe real communication skills. In practice, a learner’s tested level doesn’t always match their usable ability.

Many people technically “have” a level on paper, yet struggle to function comfortably in everyday situations.

This gap is key to assessing your true progress honestly and productively.

Test level vs usable level

A test level reflects how well you perform under exam conditions: structured tasks, familiar formats, and limited contexts.

A usable level, on the other hand, shows how confidently you can apply the language in real life. In conversations, spontaneous situations, and imperfect conditions.

It’s common to pass a level test by recognising grammar patterns or choosing correct answers, yet hesitate when speaking or listening to native-speed language

“Paper B1” vs functional B1

“Paper B1” learners can often pass a B1 exam but still struggle to hold a natural conversation, follow unscripted speech, or express ideas without long pauses.

A functional B1 learner, by contrast, can get their message across reliably. They make mistakes, but they can narrate experiences, explain opinions simply, ask follow-up questions, and cope when conversations don’t go exactly as planned.

Why confusion here is normal

This mismatch feels frustrating, but it’s completely normal.

Language skills don’t develop evenly. Reading often outpaces speaking, listening lags behind vocabulary, and confidence fluctuates.

Many learning environments prioritise test success over spontaneous use, which widens the gap. Add nerves, unfamiliar accents, or fast speech, and even strong learners can feel “lower level” than they are.

How to Assess Your Language Level Accurately

Self-assessment is one of the most powerful and most overlooked parts of language learning.

Tests and labels offer guidance. Only you can judge how confidently you use a language in real situations.

Regular reflection helps you identify strengths, spot gaps, and adjust your learning focus before frustration sets in.

Self-evaluation in language learning

Effective self-evaluation isn’t about judging yourself harshly or chasing perfection.

It’s about noticing patterns: where you hesitate, what feels automatic, and which situations cause breakdowns. Asking simple questions:

- Can I explain an idea without planning?

- Can I follow a normal conversation?

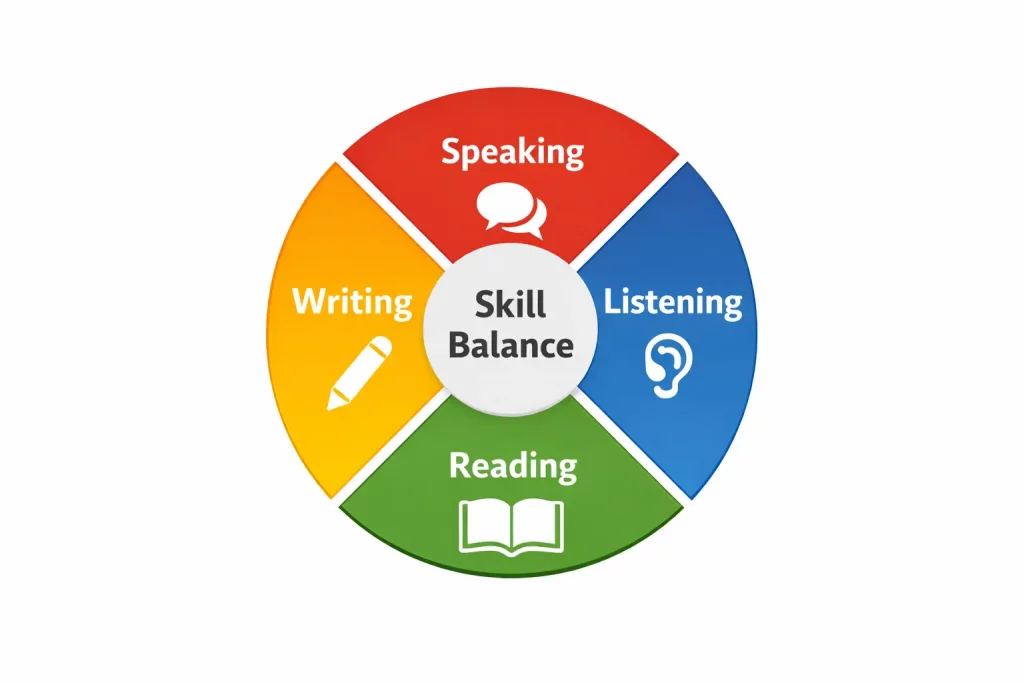

Key areas to assess: speaking, listening, reading, and writing

Each skill develops at a different pace, so assessing them separately is essential.

- Speaking: Can you express ideas without translating in your head? Do conversations flow, even with mistakes? Can you repair misunderstandings?

- Listening: Can you follow native speech at normal speed? Do you understand the main idea without catching every word? How well do you cope with different accents?

- Reading: Can you understand articles, messages, or books without constant dictionary use? Do you grasp tone and implied meaning?

- Writing: Can you write clearly and appropriately for different contexts? Are your messages easy to understand, even if not perfectly accurate?

Tools and resources for self-assessment

Several reliable tools can help you assess your level more objectively and spot gaps between what you know and what you can actually use.

- CEFR “can-do” descriptors

- Use the official CEFR self-assessment grids from the Council of Europe. These break each level into practical tasks, making it easier to judge your real ability rather than guessing based on labels.

- Use the official CEFR self-assessment grids from the Council of Europe. These break each level into practical tasks, making it easier to judge your real ability rather than guessing based on labels.

- Recorded speaking samples

- Graded readers and learner podcasts

- Tools such as Olly Richards’ graded readers, BBC Learning English, or learner podcasts like Coffee Break Languages.

- Language exchanges and real interaction

- Apps like Tandem and HelloTalk expose you to unscripted language.

- Online placement tests (used carefully)

- Placement tests from Cambridge English, EF, or Duolingo can provide a rough benchmark.

Skill Imbalance Across Language Levels

It’s rare for language learners to develop speaking, listening, reading, and writing at the same pace.

In fact, uneven progress is normal. It is often a sign that you’re actively using the language.

The key is knowing when an imbalance is a natural phase, and when it starts to hold you back.

Common imbalances

Some of the most frequent patterns include strong reading but weak speaking, good grammar knowledge with poor listening comprehension, or confident writing paired with hesitant conversation.

Many learners can understand far more than they can produce. Especially in the early and middle stages.

These imbalances often show up clearly when learners move from structured study into real-world use. This is where spontaneous speech and fast listening suddenly feel much harder than exercises or textbooks.

Why they happen

Skill imbalance is usually shaped by how and how often you practise.

Reading and grammar are easier to study alone, so they tend to advance faster.

Speaking and listening require real-time processing, tolerance of ambiguity, and emotional confidence. Which slows progress.

When an imbalance blocks progression

Imbalance becomes a problem when one weak skill limits everything else.

For example, poor listening can make conversations exhausting, even if your vocabulary is strong. Weak speaking fluency can prevent you from using grammar you technically know, creating the feeling of being “stuck”.

When it doesn’t

Not all imbalance is negative.

If you’re reading far ahead of your speaking level, you’re still building vocabulary, intuition, and exposure that will later support fluency.

Temporary imbalance is especially normal after breaks, intensive reading phases, or exam-focused study.

The key indicator is functionality: if you can still communicate effectively for your goals, an imbalance isn’t a failure. It’s a phase.

Consistency and Progress Through Language Levels

Consistency is one of the strongest predictors of long-term success in language learning.

While intensity can accelerate progress in short bursts, it is regular, repeated exposure that turns knowledge into an automatic skill.

The role of regular practice in language acquisition

Language acquisition depends on repeated contact with sounds, structures, and meaning over time.

Regular practice strengthens neural pathways. Making comprehension faster and production more automatic.

Short, frequent sessions are generally more effective than infrequent, long study blocks.

Signs that you are consistently using the language

Consistency shows itself through gradual, often quiet changes rather than sudden breakthroughs.

When you use a language regularly, progress becomes noticeable in how natural things feel, not just in how much you know.

- You recognise words, phrases, and sentence patterns without needing to analyse them

- You hesitate less when starting conversations or responding

- You understand the main idea of spoken or written content, even if you miss details

- You repeat the same mistakes less often or correct yourself automatically

- The language feels less intimidating and more familiar

- You are more willing to speak or engage, even when tired or unsure

How to track your practice and progress

Tracking does not need to be complex to be effective. Simple systems work best when they are easy to maintain.

Many learners benefit from a basic habit log, noting daily or weekly exposure to speaking, listening, reading, and writing. Others track concrete outcomes, such as minutes spoken, pages read, or episodes understood.

Periodic self-checks using CEFR-style “can-do” statements help link effort to real ability.

Comfort with Current Level

Feeling comfortable at a particular language level is a natural stage in the learning process.

It often signals that foundational skills are settling and that the language is becoming more familiar.

However, comfort can mean different things. Recognising what it represents helps you decide whether to consolidate or push forward.

Recognising when you feel comfortable with your current level

Comfort usually shows up as reduced mental effort.

You no longer need to plan every sentence in advance, and common interactions feel predictable rather than stressful.

You can follow routine conversations, understand familiar content, and respond without constant hesitation.

Signs that you have mastered the basics

Mastering the basics means your language use is dependable rather than flawless. You may still make mistakes, but they no longer prevent communication.

Everyday situations feel manageable, and you can focus more on meaning than on constructing language itself.

- You can communicate core ideas clearly without excessive planning

- You handle routine situations with confidence and minimal stress

- You understand the main points of everyday speech at a natural pace

- You use common grammatical structures consistently, even if imperfectly

- You rely less on your native language to fill gaps

- You feel ready to expand beyond survival language into richer expression

The balance between comfort and challenge

Comfort is valuable because it builds confidence and reinforces habits.

However, staying too comfortable for too long can slow progress. Growth happens when familiar skills are gently stretched by new vocabulary, faster speech, or more complex ideas.

Why Language Progress Slows at Higher Levels

Most language learners eventually reach a point where progress seems to slow or even stop.

You are studying, practising, and engaging with the language, yet nothing feels noticeably better.

This stage is frustrating. It is also one of the most normal and misunderstood parts of language learning.

Why progress feels slower

In the early stages, progress is obvious.

You go from knowing nothing to understanding and using basic phrases, which feels dramatic.

As your level rises, improvements become more subtle. Gains show up as smoother comprehension, fewer hesitations, or better accuracy rather than new, visible “milestones”.

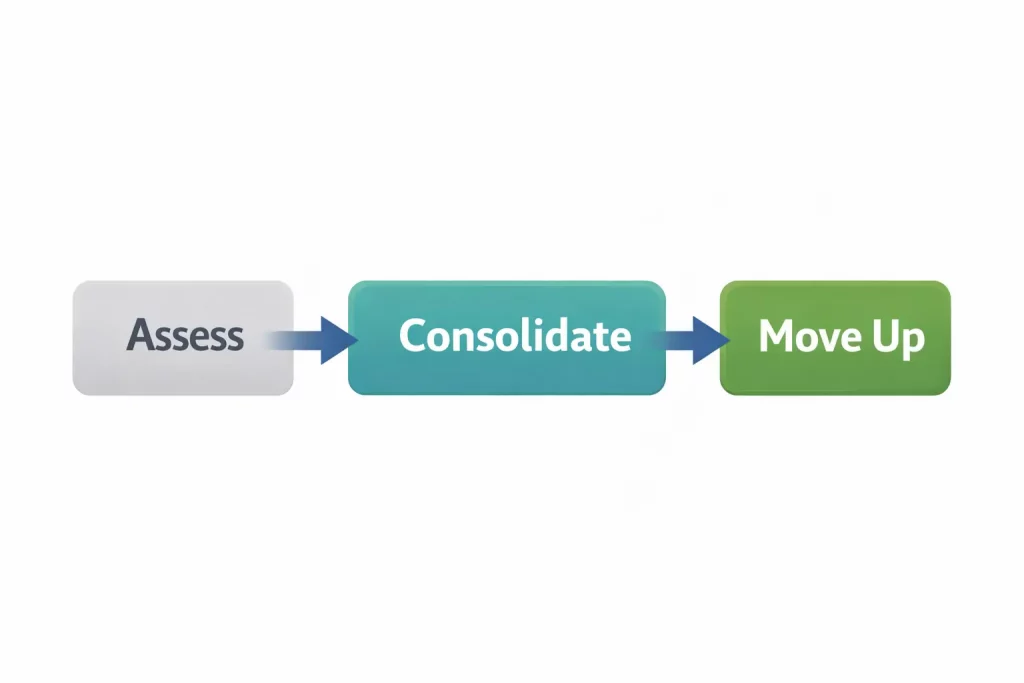

What are the language consolidation phases?

Language consolidation phases are periods where the brain is organising and reinforcing what you already know.

Instead of adding large amounts of new vocabulary or grammar, your skills are becoming more stable, automatic, and flexible.

Why plateaus often precede breakthroughs

Breakthroughs rarely happen without consolidation first.

When enough patterns, vocabulary, and experience accumulate, skills suddenly start working together more smoothly.

Speech feels easier, listening improves rapidly, or confidence jumps seemingly overnight.

Common Signs You’re Not Ready Yet

Moving up a level too quickly can feel tempting, but readiness is about stability, not ambition.

When key skills are still fragile, progress at the next stage often feels stressful rather than motivating. However, this is normal.

These signs show you’re not ready yet:

- You struggle to express basic ideas without long pauses or mental translation

- You rely heavily on memorised phrases instead of flexible language use

- You understand individual words but miss the overall meaning in conversations

- You feel lost when discussions move beyond familiar topics

- Your performance varies greatly depending on mood, energy, or pressure

- Speaking or listening still feels exhausting rather than manageable

Want language learning to finally feel clear?

Join Language Learners Hub for practical explanations, honest guidance, and realistic advice on how languages are actually learned — without hype or shortcuts.

Subscribe for free →Occasional emails. No spam. Always useful.

Feedback from Others

External feedback plays a crucial role in language learning. It shows you what you cannot easily see in yourself.

While self-assessment builds awareness, feedback from others provides perspective, helping you judge whether your skills are stable enough to move forward or still need consolidation.

Importance of external feedback in language learning

When you use a language, your focus is often on meaning and survival rather than accuracy or clarity.

Teachers, tutors, and peers can notice recurring patterns, fossilised errors, or gaps in comprehension that you may overlook.

How to seek constructive criticism from teachers or peers

Constructive feedback works best when it is specific and targeted.

Instead of asking whether your language is “good”, ask focused questions such as whether your ideas are clear, which mistakes interfere with understanding, or what skill is currently holding you back.

Recording short speaking samples, sharing written work, or requesting feedback on real interactions gives reviewers something concrete to assess.

Language exchanges and tutors are especially useful when you clearly state your goals and invite correction rather than general praise.

Engaging with Native Speakers

Engaging with native speakers is one of the clearest tests of how usable your language really is.

It moves learning beyond controlled exercises into real communication, where speed, unpredictability, and cultural nuance come into play.

Benefits of conversing with native speakers

Speaking with native speakers pushes your language skills into real-world conditions.

It exposes you to how the language is actually used day to day, helping you move beyond textbook patterns and develop flexibility, confidence, and listening resilience.

- You hear natural rhythm, pronunciation, and connected speech in real time

- You encounter fillers, interruptions, idioms, and informal phrasing

- You learn how people really start, maintain, and end conversations

- Your listening skills strengthen under natural speed and unpredictability

- You build confidence in coping with gaps rather than freezing

- You learn to adapt, rephrase, and keep conversations moving

How to find opportunities for real-life practice

Opportunities for real-life practice are more accessible than many learners expect. Language exchange apps like Tandem and HelloTalk connect you with native speakers worldwide for casual conversation.

For more structured practice, platforms such as italki and Preply offer guided conversation with feedback. In-person options include local language meet-ups, cultural events, or community groups.

Complex Language Concepts

As learners progress, language learning shifts from mastering survival skills to handling nuance, abstraction, and precision.

Being ready for more complex concepts means your foundation is stable enough to support deeper grammar, richer vocabulary, and more flexible expression.

Recognising when you can grasp more complex grammar and vocabulary

You are ready for more advanced concepts when basic structures no longer require conscious thought.

You can follow explanations that build on what you already know, and new grammar feels like an extension rather than a reset.

Other signs include noticing patterns in authentic content, asking “why” questions about usage, and wanting to express ideas more precisely.

Examples of advanced concepts to master before moving up

Advanced concepts vary by language. They often include more nuanced grammar and broader lexical control.

Common examples include managing multiple past tenses accurately, expressing hypotheses and conditions, using connectors to structure complex ideas, and understanding aspects or registers.

The importance of expanding your language knowledge

Expanding knowledge is not about memorising rules for their own sake.

It increases precision, flexibility, and comprehension across all skills.

A wider grammatical and lexical range lets you understand more complex input and express subtle differences in meaning.

Emotional Readiness

Progressing to a higher language level is not only a technical decision. It also involves emotional readiness.

Confidence, self-perception, and comfort with uncertainty all influence whether moving forward feels empowering or discouraging.

Confidence vs competence

Confidence and competence do not always develop at the same pace.

Some learners feel confident early, even when skills are fragile, while others are highly competent but hesitate to speak.

Emotional readiness means having enough confidence to use the language imperfectly while continuing to learn.

| Aspect | Confidence | Competence |

| What it reflects | How comfortable you feel using the language | How well you can actually use the language |

| How it develops | Often influenced by personality and past experience | Built through practice, exposure, and consolidation |

| Common pattern | Can appear early, even with limited ability | May grow quietly before learners feel ready to speak |

| Typical risk | Overestimating ability and moving on too fast | Underestimating ability and holding back unnecessarily |

| Impact on progress | Encourages participation but may mask gaps | Ensures accuracy but may limit real use |

| Role in readiness | Provides the courage to speak imperfectly | Provides the foundation to communicate reliably |

| Ideal balance | Confidence supports experimentation | Competence supports clarity and stability |

| True readiness | Using the language despite mistakes | Communicating effectively without fear |

Fear of sounding worse

As you move beyond the basics, you often attempt more complex ideas.

This can temporarily make your speech sound less polished than before. Many learners misinterpret this as regression.

In reality, this phase reflects growth. You are stretching your language and taking risks.

Identity shift

Advancing in a language involves an identity shift.

You stop seeing yourself as “someone who knows a bit” and start acting as a user of the language.

This shift can feel uncomfortable, especially when your personality does not yet fully come through.

Emotional readiness means allowing yourself to sound simpler than you are intellectually, trusting that expression will catch up. This acceptance frees you to engage more fully and progress with confidence.

When Not to Move Up

Moving up a level is not always the most effective choice.

In some cases, staying where you are and deepening your skills leads to stronger, more durable progress.

Knowing when not to advance is a strategic decision. Not a setback.

Strategic consolidation

Strategic consolidation means deliberately strengthening what you already know before adding new complexity.

This might involve improving fluency, accuracy, or confidence within your current level. Rather than chasing new grammar or vocabulary.

When depth beats progression

Depth beats progression when surface-level advancement creates fragility.

If you move up without fully mastering core structures, conversations become stressful and comprehension unreliable.

Long-term fluency benefits

Long-term fluency depends on stability. Languages used confidently over time are built on well-consolidated skills rather than rushed progression.

Learners who prioritise depth tend to retain more, self-correct naturally, and adapt better in real situations. Resisting the urge to move up too soon, you invest in fluency that lasts rather than progress that feels impressive.

Language Level Readiness Checklists (A1 to C1)

Moving between language learning levels is not just about finishing a course or ticking off grammar points.

Each transition represents a shift in how you use the language, how much independence you have, and how well your skills hold up in real situations.

These level-specific readiness checklists are designed to help you judge whether your current abilities are stable enough to support the next stage.

A1 → A2: Ready to Move Beyond the Basics?

This transition is about moving from survival language to simple, functional communication. If you can do most of the following comfortably and consistently, you are likely ready to progress. You do not need perfection, but your foundations should feel stable.

Communication & Speaking

- You can introduce yourself and others without relying entirely on memorised scripts

- You can ask and answer simple questions about daily life, routines, work, or family

- You can link short sentences together rather than speaking only in single words

- You can manage basic interactions such as ordering food, shopping, or asking for directions

Listening & Comprehension

- You understand slow, clear speech on familiar topics without constant repetition

- You can follow short conversations when the context is clear

- You recognise common everyday phrases, even if you miss some details

Vocabulary & Grammar Foundations

- You use basic verb forms with some consistency (present tense and simple past or future expressions)

- You can use common connectors such as “and”, “but”, and “because”

- You have enough everyday vocabulary to express basic needs and ideas without stopping every sentence

Comfort & Functional Readiness

- You worry less about making mistakes and focus more on being understood

- You can keep short interactions going, even when unsure

- You feel ready to practise more freely rather than memorise more phrases

A2 → B1: Ready to Use the Language Independently?

Moving from A2 to B1 marks a major shift. At this stage, you move beyond guided, predictable interactions and begin using the language with real independence.

B1 is often the point where a language starts to feel genuinely usable in everyday life.

Communication & Speaking

- You can hold short conversations on familiar topics without relying on memorised phrases

- You can describe experiences, plans, and opinions using connected speech

- You can keep a conversation going by asking simple follow-up questions

- You can get your point across even when you lack precise vocabulary

Listening & Comprehension

- You understand the main points of everyday conversations at a natural pace

- You can follow short talks, videos, or podcasts on familiar subjects

- You cope with normal speech even if you miss some details

Vocabulary & Grammar Foundations

- You can use common past, present, and future forms to talk about time and events

- You can link ideas using basic connectors such as “because”, “although”, and “so”

- You have enough vocabulary to talk about work, travel, interests, and daily life

Comfort & Functional Readiness

- You feel able to manage most routine situations without help

- You can continue speaking even when you make mistakes

- You feel ready to use the language outside structured lessons

B1 → B2: Ready for Real Conversations and Complexity?

The move from B1 to B2 is where a language shifts from usable to comfortable. At B2, you are no longer just managing situations.

You can participate, react, and express yourself with greater range and confidence, even when conversations become less predictable.

Communication & Speaking

- You can hold conversations on a wide range of familiar topics without excessive hesitation

- You can explain opinions, give reasons, and react to what others say in real time

- You can adapt your wording when you do not know the exact expression

- You can sustain conversations for longer periods without mental fatigue

Listening & Comprehension

- You understand the main ideas of extended speech at natural speed

- You can follow discussions, films, or podcasts without needing constant clarification

- You cope reasonably well with different accents or speaking styles

Vocabulary & Grammar Foundations

- You use a broad range of vocabulary to discuss abstract or non-personal topics

- You can handle more complex grammar, such as conditionals, reported speech, or nuanced past forms

- You link ideas clearly using a variety of connectors and discourse markers

Comfort & Functional Readiness

- You feel comfortable participating in group conversations

- You can express disagreement, uncertainty, or nuance without shutting down

- You use the language regularly in real contexts, not just study sessions

B2 → C1: Ready for Nuance, Precision, and Flexibility?

Moving from B2 to C1 is less about learning more language and more about using it better.

At this stage, the focus shifts to precision, subtle meaning, and adaptability across contexts.

C1 users can handle complexity without strain and adjust their language to suit purpose, audience, and tone.

Communication & Speaking

- You can express complex ideas clearly and spontaneously with minimal hesitation

- You can adjust your language for formal, informal, and professional situations

- You can explain abstract concepts, opinions, and arguments in detail

- You can speak flexibly, reformulating ideas when needed, without losing fluency

Listening & Comprehension

- You understand extended speech even when it is fast, idiomatic, or loosely structured

- You follow debates, lectures, and discussions on unfamiliar or abstract topics

- You rarely need repetition or simplification to grasp meaning

Vocabulary & Grammar Foundations

- You have a broad and precise vocabulary, including collocations and idiomatic expressions

- You use complex grammatical structures accurately and naturally

- You can manipulate language to create emphasis, contrast, and nuance

Comfort & Functional Readiness

- You feel comfortable using the language in professional or academic contexts

- You can maintain your identity and personality in the language

- You use the language flexibly across reading, writing, listening, and speaking

Setting New Goals

Reaching a new level is not the end of the journey. It is the moment to reset direction.

Clear, well-chosen goals help you move forward with purpose, prevent stagnation, and ensure that progress at the next level feels meaningful rather than unfocused.

How to set realistic and achievable goals for the next level

Effective goals are specific and grounded in real language use.

Instead of aiming vaguely to “reach B2” or “be fluent”, focus on outcomes you can observe.

As an example, it could be holding a 15-minute conversation, understanding a podcast without subtitles, or writing clear emails on familiar topics.

Importance of aligning goals with your interests and needs

Goals are more sustainable when they connect to your life. Learning a language for travel, work, relationships, or study creates natural motivation and relevance.

When goals reflect what you actually want to do with the language, practice feels purposeful rather than forced.

Strategies for maintaining motivation during the transition

Moving up a level often feels harder before it feels better. As complexity increases, progress can seem slower and confidence may dip.

Staying motivated during this phase means focusing on stability, small improvements, and sustainable habits rather than dramatic leaps.

- Set short-term, skill-specific goals instead of broad-level targets

- Track small wins, such as smoother conversations or better comprehension

- Rotate between different practice types to avoid fatigue and boredom

- Revisit easier material occasionally to reinforce confidence

- Use regular self-checks to notice progress that is not immediately obvious

- Prioritise consistency over intensity to keep the language active

How to Move Up a Language Level Successfully

Moving up a level works best when you change how you study, not just what you study.

This phase is about recalibrating your inputs, outputs, and expectations so your learning matches the demands of the next level..

What to Change in Your Study Materials

At a new level, materials should stretch comprehension, not confirm it. If everything feels comfortable, the input is no longer doing its job.

The key shift is moving:

- From graded content to semi-authentic, and then increasingly authentic material

- From slow, clear language to natural speed, with real rhythm and imperfection

- From controlled examples to incomplete understanding, where you follow the meaning without catching every word

- From a single “standard” variety to different accents, registers, and styles

At the same time, it is usually time to reduce:

- Beginner-style drills and highly scaffolded exercises

- Isolated grammar practice that never reaches real use

- Overly safe content that feels fluent but teaches little

How Your Practice Balance Should Shift

This is where many learners stall. As language learning levels increase, progress depends less on recognition and more on production and control.

A useful way to think about the shift:

- Beginner stages: input-heavy, guided output

- Intermediate stages: more balanced input and output

- Upper-intermediate and beyond: output-led practice, supported by feedback

In practical terms, this means:

- Fewer short, disconnected exercises and more sustained tasks

- Longer speaking turns instead of quick answers

- Writing and speaking that require organising ideas, not filling gaps

- Greater tolerance for errors while focusing on clarity and structure

What the Adjustment Period Will Feel Like

This phase often feels uncomfortable, and that is not a problem. It is a signal that your learning is recalibrating.

Common experiences include:

- A temporary drop in confidence

- Feeling less fluent even though you are learning more

- Slower comprehension as input becomes richer and less predictable

- Increased awareness of gaps you did not notice before

This connects directly to earlier ideas around plateaus, consolidation, and emotional readiness.

Feeling “worse” often means you are finally seeing the language more clearly. Your skills are adjusting to higher demands, not disappearing.

Questions Learners Ask Before Moving Up a Level

How do I know when I am ready to move up a level?

You are usually ready when your skills feel stable, not perfect. You can use the language consistently in real situations, recover from mistakes, and handle familiar tasks without excessive effort or preparation.

Is it normal to feel less confident when moving up?

Yes. Confidence often dips during transitions because the language you are exposed to becomes faster, richer, and less predictable. This discomfort is a normal sign of adjustment, not a sign that you are getting worse.

Can I move up if one skill is weaker than the others?

Small imbalances are normal. However, if one skill consistently blocks communication, most commonly listening or speaking, it is usually better to consolidate that area before progressing.

How long should I stay at each level?

There is no fixed timeline. Progress depends on the quality of exposure, consistency, and your goals. Readiness matters far more than how long you have been studying or how many courses you have completed.

Do I need to master all grammar before moving up?

No. Language learning levels are based on use, not complete grammatical knowledge. You should be able to use core structures reliably, even if accuracy is not perfect.

What if I move up and realise it is too difficult?

That is not failure, it is feedback. Stepping back to consolidate is a strategic choice and often leads to faster, more confident progress when you move up again.